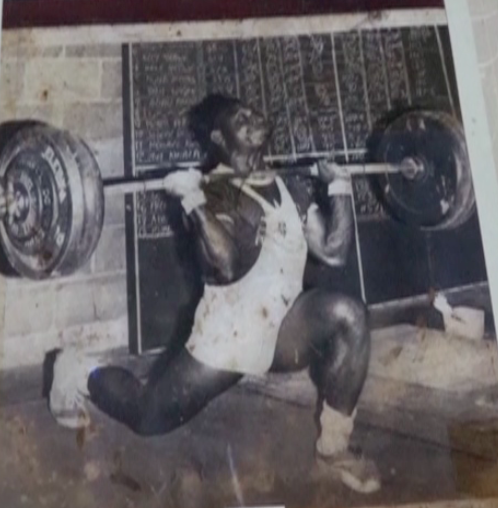

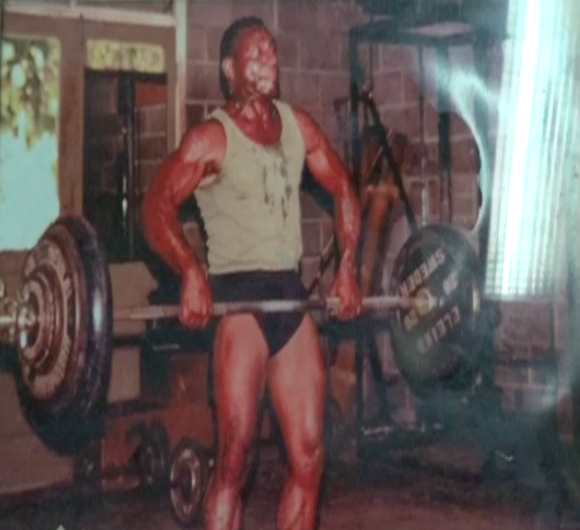

A pioneering sportsman and weightlifter, Michael Mexico has kept a secret for 53-years of how Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare and wife Lady Veronica bestowed the name ‘Michael Mexico’ to him in 1968.

Upon hearing Grand Chief’s passing he felt it was time he shared the story with everyone -a story only he and his family members knew for 53-years.

In 1968, 24-year-old Michael represented Papua New Guinea (then it was known as New Guinea) in an International Sporting event in Mexico.

He won a Bronze Medal ( the first Papua New Guinean to win a medal at an International Sporting Event).

He was scheduled to travel from Mexico to Sydney then to Canberra, where he was studying as a student. However, his flight was diverted and landed at Jacksons’ Airport.

“Upon my arrival at Jacksons Airport, Lady Veronica and Sir Michael Somara greeted me as “Michael Mexico! Welcome from Mexico,” recounted Mexico.

From then on, he changed his name to Michael Mexico.

He joined the nationwide tributes to the late Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare.

“To Lady Veronica, I am sorry for your husband’s passing.”

“It is also a loss for the rest of PNG.” He added.

After 1968, Mexico went on to win a gold medal in the 1969 South Pacific Games and many medals after that in Tahiti, Guam, Fiji, Western Samoa, and Brisbane.

He retired from weightlifting in 1982. And now lives in Lae, Morobe Province.