Discussions at the National Planning Consultative Summit in Lae have revealed how Papua New Guinea’s national population policies have fallen short of stemming population growth.

Some of the problems highlighted were the lack of access, understanding, and the conflicting views on contraception between government and churches.

While much of the talk revolved around economic growth, there was a stark reminder that population growth rate at more than 3 percent per annum needed to be controlled.

On average, 300,000 children are born every year. If Papua New Guinea continues to have an economy that doesn’t surpass that growth, basic services will become seriously burdened.

But the signs are already evident. Urban clinics continue to be overburdened with the influx of patients. Health workers admit that urban populations have risen over 30 years.

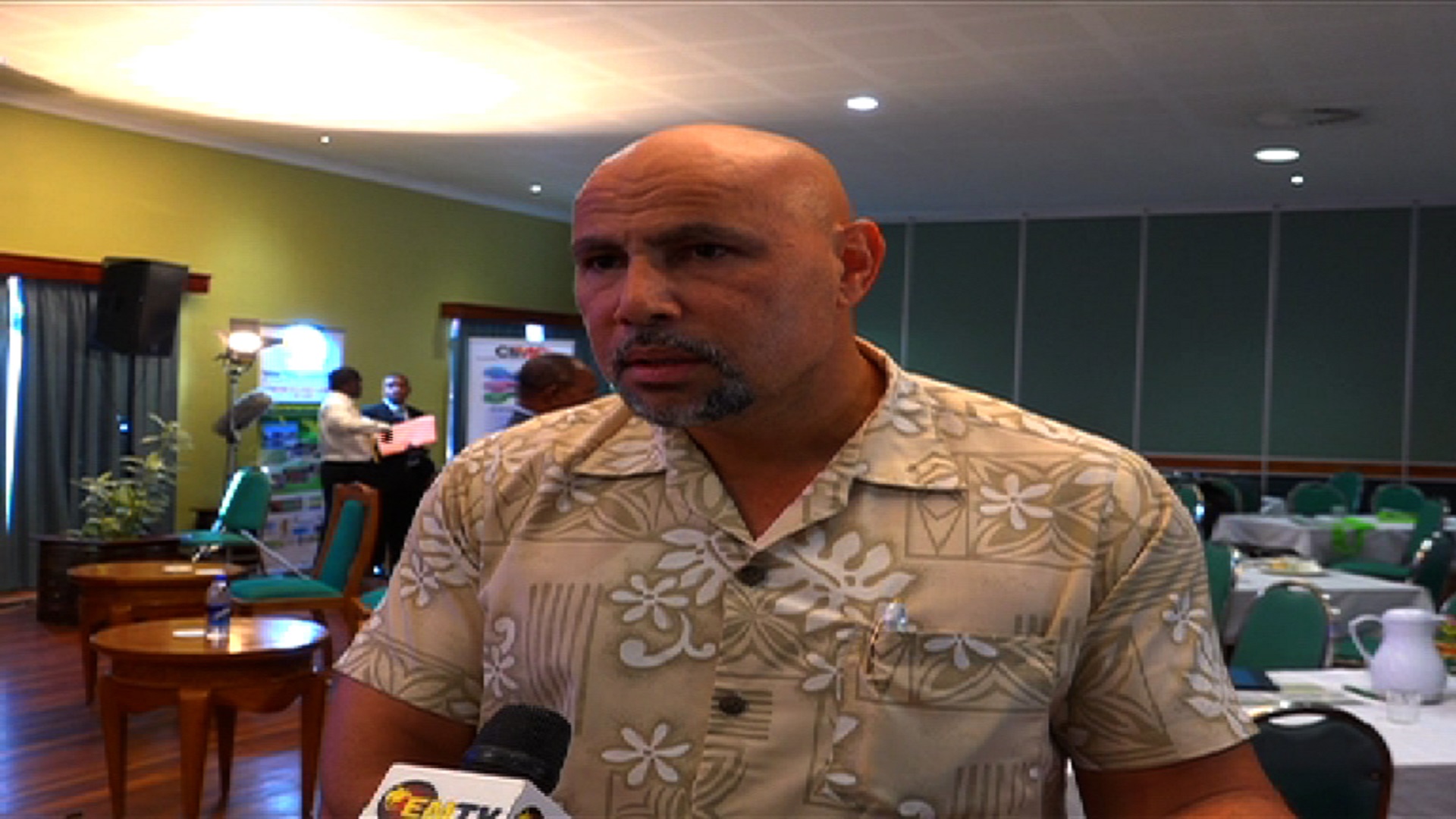

In the last term of government, Deputy Prime Minister, Charles Abel, launched a population control strategy. While he admits there are weaknesses, he maintains there is more awareness now than before.

“The policy that I launched should be matched up with the implementation document which is the document two of the population policy. The implementation also has to happen in the district and ward level as well.”

In many rural areas, contraception and family planning are of a lesser priority than curative health.

“Contraception is supposed to be free for those who want it,” says Geoffrey Hayes, a population and development specialist at the UNFPA.

“But health workers still charged people who sought help because they didn’t know about the government policy.”

With roughly 40 percent of health services operated by the Catholic Church, government policy has in many instances come into conflict with the church’s views on contraception.

Government policies on population control and the use of contraception is at times a touchy subject.

Even politicians realise that the conflict could potentially extend to the polling booths if the more than 2 million Papua New Guinean Catholics disagree with the government.

In February, the Catholic Bishop of Alotau, Ronaldo Santos, told the ABC’s Pacific Beat Program “They should not use artificial means in order to prevent the natural process from taking place.”

“I’ve had my own clashes with the Catholic Church. But with a more liberal Pope, I think the church is slowly changing its views,” Charles Abel says.