by Terence Wood

Long ago, in a country many miles from where I currently sit, I worked on an aid project. It has stuck with me over the years: a suite of lessons about what can go wrong with aid. Some of the problems were huge. Some were more human in scale. The person I reported to, for example. He was energetic and smart, and simultaneously a relic of a by-gone era.

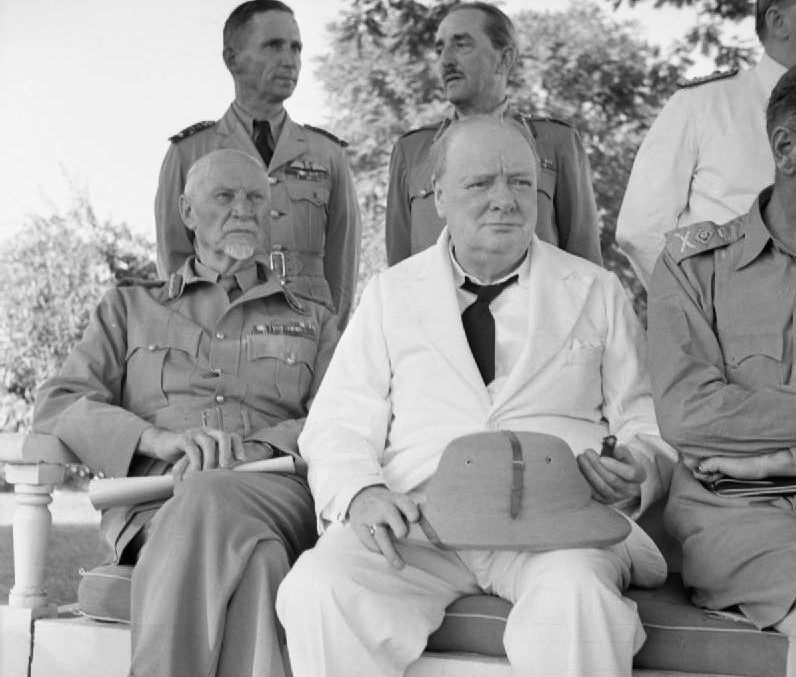

When he spoke to people from the country we were working in the often sounded arrogant. Worse, he showed no interest in what his local counterparts knew. There were times when I used to look at him and think, “buddy, all you need is a pith helmet”.

I was reminded of this man last year when someone told me aid was “neo-colonial”. The idea is common in parts of academia. And complaints about colonial traits were some of the scattered shots taken at aid in a recent scattershot New York Times Op-Ed.

As with other accusations leveled at aid (neoliberism, for example), what people mean when they say ‘neo-colonial’ or ‘colonial’ isn’t always clear. Usually though, neo-colonial refers to one of two, potentially related, problems with aid.

The first fits with the dictionary definition of neo-colonial: aid is neo-colonial because it’s used to subjugate recipients, while donors profit from the power they gain.

The second pertains to a subtler power imbalance. International aid workers are neo-colonial because – like the colonial administrators of yore – they’re too taken with their own ideas, and don’t appreciate the knowledge of people in the countries where they work. Worse still, they are unwilling to hand power over to local actors, and let locals use aid as they see fit.

Both of these accusations aren’t entirely wrong. But they’re not entirely right either.

At times, government aid has been part of a neo-colonial dynamic of the first sort. The relationship between the United States and Latin American countries provides examples of this. But for most donors, most of the time, aid doesn’t afford enough power for quasi-colonial subjugation to occur. Donor power increases when recipients face economic crises, yet these moments are rare. Otherwise, donors simply don’t give enough aid to gain much leverage. In 2018, aid from all OECD DAC donors to the median aid recipient country was just 1.27% of its Gross National Income. Even in the Americas, the United States’ influence never came from aid alone: it required the CIA, military, diplomats, and allied local elites.

Aid doesn’t build neo-colonial relationships in the classic sense. Government aid donors do – too often – pursue their own national interest when giving aid. Aid is worse as a result. But pursuit of the national interest usually involves procuring international alliances, and subsidising donors’ firms, not subjugating other states.

The second accusation is clearly sometimes true, as my former colleague Pith Hat demonstrated. But even his story wasn’t that simple. He’d stumbled into the role; he wasn’t an experienced aid worker. The actual aid workers involved in the project were usually different. They weren’t perfect: like me, they possessed human flaws. But they didn’t behave like viceroys. The project wasn’t solely staffed by international staff either, and it was run in collaboration with a local organisation. It’s true, the donor hadn’t just handed money to the recipient and butted out, which is what the New York Times Op-Ed argues for. Sometimes this is an excellent idea. But it isn’t always. This project was large. It spanned multiple levels of government, and local communities. At every level there was a risk that local elites would tap into the project for their own ends. That may sound harsh. But it’s also true of elites in my home country. Without checks and balances, power consumes money. In aid, sometimes this means donors need to be actively involved.

At its worst, aid does seem maddeningly colonial. But the semblance isn’t everything. Often aid isn’t that bad. And when it is, the real issues are usually different.

In the case of the project I worked on, the biggest problem was a donor country with geostrategic goals. As a result, it was desperate that aid didn’t rock the political boat. The trouble was, productive political engagement was needed if the real problems we were meant to be helping with were ever going to be addressed.

Some of the staff were also – obviously – not fit for their roles. Yet as I said, most were good. But they were also time-pressured and called on to do too much. This meant nothing – including respectful relationships with local counterparts – got the attention it needed. Learning systems were threadbare too. As a result, problems got to hide in plain sight, while the project never became any wiser or better designed.

These aren’t very exciting woes. I couldn’t write an Op-Ed about them. But such is the complexity of aid and its faults. Seeing these faults for what they are is important. Because some aid is much better than the project I worked on. Sometimes it really helps. And that’s the change we should be pushing for.

Disclosure:Terence Wood’s research on aid is undertaken with the support of The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The views expressed here are those of the author only.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University.

Terence Wood is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. His research focuses on political governance in Western Melanesia, and Australian and New Zealand aid.