by Rohan Fox

Papua New Guinea has been in the grip of foreign exchange shortages and rationing for the last six years. This has been listed by a Business Advantage PNG survey of business leaders as one of the top five concerns for business every year since 2014, and the top concern in 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2020.

I have written about this problem since 2015, and it is disheartening to see the impact of shortages on the ground — making worse an economic environment in which many people are losing their jobs, or finding it ever more difficult to find one.

Recent estimates of delays to access to foreign exchange are between three and 12 weeks. They have been longer in the past, while some businesses are unable to access funds at all. Overall, there is no suggestion that the problem is getting better.

A recent illustration of the cost of this problem came with the announcement early this year by Virgin Airlines that it has ceased flying to Papua New Guinea, while continuing flights to much smaller Pacific destinations like Apia, Honiara, Port Vila, Rarotonga, and Nadi. While there could be various reasons for this, an August 2020 Administrator’s report to Virgin Australia creditors noted 7 million USD equivalent it was unable to transfer out due to foreign exchange shortages. Despite being by far the largest country in the Pacific and the closest to Australia, and with greater engagement between the two countries, PNG finds itself with declining international services.

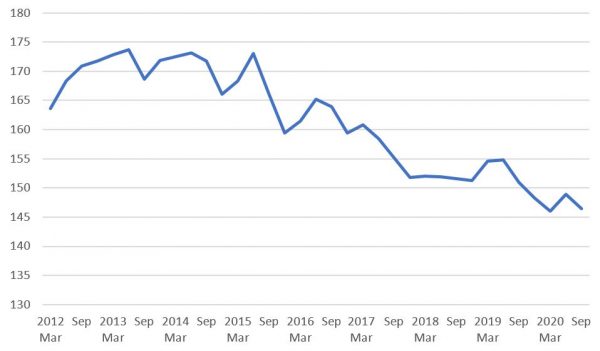

Importantly, this is not just a problem for large businesses. In fact, some of the larger companies with better relationships with government may be more able to access forex than smaller ones. As a whole, private sector employment has been falling consistently for the past six years. While job losses over the last year were inevitable given the effect of COVID-19, the decline was significant even prior to this.

Figure 1: Private sector employment index in Papua New Guinea 2012-2020 (2002=100)

PNG is dependent on commodity exports. 77 per cent of PNG’s export revenues come from mining and minerals resources, and 17 per cent from agricultural commodities. With the fall in commodity prices at the start of this decade and especially the fall in oil prices in 2014, it is not surprising that foreign currency into the country fell. Normally, one would expect the real exchange rate to change to help the economy to adjust. But as the graph below shows, the real exchange rate is unchanged since 2012.

Generally the exchange rate is presented in terms of foreign currency units, thus emphasising the perspective of people in PNG interested in purchasing foreign goods. However, it is just as valid to present the exchange rate in terms of local currency units, emphasising the perspective of businesses and employees of domestic industries who compete with imports, or who earn foreign currency and exchange it for kina — for example exporters of coffee, cocoa, vanilla or palm oil. In this article I have chosen the latter, and will make the distinction through the use of the acronym LCU (local currency units). I believe that this method emphasises the improved opportunities for these producers arising from the end of the resource boom, rather than just the costs, and in doing so highlights the balancing, counter-cyclical role that the exchange rate shouldplay.

Figure 2: Nominal and real exchange rates kina to USD 2002-2019

In Figure 2 we see that although the nominal exchange rate in local currency units has appreciated (i.e. depreciated in foreign currency units), the real exchange rate has stayed stagnant. It should be moving up too.

In other words, the increase in the nominal LCU exchange rate has not been enough. The real exchange rate takes into account both nominal exchange rate movement and inflation. PNG has had higher inflation so a certain amount of nominal LCU appreciation keeps the rate at which one can exchange goods between trading partners the same — even though the prices are now different.

With the fall in commodity and especially oil prices, there is less foreign exchange flowing in. So — beyond just the differences in inflation — without a further increase in the LCU exchange rate to encourage PNG exporters and discourage imports, it is no surprise that there will be some shortages and rationing.

Papua New Guinean MPs often say that they want to improve livelihoods in rural areas. An appreciation in the LCU exchange rate would lead to an increase in inflows to rural economies, compared to the forex rationing situation, as agricultural exporters would get more kina in exchange for their goods.

Two common solutions proposed to bring in foreign exchange are to speed up the approval of upcoming resource projects and to require companies to keep more funds onshore. The problem with the first solution is that these agreements tend to be highly complex. For example, PNG has been “waiting” now for almost a decade for the next big project. There needs to be a better approach, an approach which is quicker, over which the Government has greater control, and which doesn’t have such a negative impact on businesses.

The problem with the second solution — requiring companies to hold more funds onshore — is that if you force companies to hold funds in kina and they don’t want to, you will increase the kina in the market but you will also increase the demand for dollars, so the underlying problem of rationing remains, as the current situation demonstrates. And as the Virgin Airlines story shows, some companies will remove services, which results in fewer employment opportunities.

PNG has tried for six years to solve the foreign exchange rationing problem without trying a real appreciation in local currency terms. This approach has kept the price of foreign goods from climbing higher, but it has also exacerbated the decline in employment.

With the problem of rationing continuing, it is time to try a new strategy. The most efficient and sustainable way to end the problem of foreign exchange rationing is to give agricultural exporters and PNG businesses competing with imports an incentive to expand, create employment and produce more Papua New Guinean goods; and importers an incentive to purchase less from overseas. Disclosure: This research was undertaken with the support of the ANU-UPNG Partnership. The views are those of the author only.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University.

Rohan Fox is a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre. He lectured in the economics program at the University of Papua New Guinea in 2015, 2016 and 2020.