Apple on Thursday unveiled changes to iPhones designed to catch cases of child sexual abuse, a move that is likely to please parents and police but that was worrying privacy watchdogs.

Later this year, iPhones will begin using complex technology to spot images of child sexual abuse, commonly known as child pornography, that users upload to Apple’s iCloud storage service, the company said. Apple also said it would soon let parents turn on a feature that can flag when their children send or receive nude photos in a text message.

Apple said it had designed the new features in a way that protects the privacy of users, including by ensuring that Apple will never see or find out about any nude images exchanged in a child’s text messages. The scanning is done on the child’s device, and the notifications are only sent to parents’ devices. Apple provided quotes from some cybersecurity experts and child safety groups who praised the company’s approach.

Other cybersecurity experts were still concerned. Matthew Green, a cryptography professor at Johns Hopkins University, said Apple’s new features set a dangerous precedent by creating surveillance technology that law enforcement or governments could exploit.

“They’ve been selling privacy to the world and making people trust their devices,” Green said. “But now they’re basically capitulating to the worst possible demands of every government. I don’t see how they’re going to say no from here on out.”

Apple’s moves follow a 2019 investigation by The New York Times that revealed a global criminal underworld that exploited flawed and insufficient efforts to rein in the explosion of images of child sexual abuse. The investigation found that many tech companies failed to adequately police their platforms and that the amount of such content was increasing drastically.

While the material predates the internet, technologies such as smartphone cameras and cloud storage have allowed the imagery to be more widely shared. Some imagery circulates for years, continuing to traumatize and haunt the people depicted.

But the mixed reviews of Apple’s new features show the thin line that technology companies must walk between aiding public safety and ensuring customer privacy. Law enforcement officials for years have complained that technologies like smartphone encryption have hamstrung criminal investigations, while tech executives and cybersecurity experts have argued that such encryption is crucial to protect people’s data and privacy.

In Thursday’s announcement, Apple tried to thread that needle. It said it had developed a way to help root out child predators that did not compromise iPhone security.

To spot the child sexual abuse material, or CSAM, uploaded to iCloud, iPhones will use technology called image hashes, Apple said. The software boils a photo down to a unique set of numbers — a sort of image fingerprint.

The iPhone operating system will soon store a database of hashes of known child sexual abuse material provided by organizations like the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, and it will run those hashes against the hashes of each photo in a user’s iCloud to see if there is a match.

Once there are a certain number of matches, the photos will be shown to an Apple employee to ensure they are indeed images of child sexual abuse. If so, they will be forwarded to the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, and the user’s iCloud account will be locked.

Apple said this approach meant that people without child sexual abuse material on their phones would not have their photos seen by Apple or the authorities.

“If you’re storing a collection of CSAM material, yes, this is bad for you,” said Erik Neuenschwander, Apple’s privacy chief. “But for the rest of you, this is no different.”

Apple’s system does not scan videos uploaded to iCloud even though offenders have used the format for years. In 2019, for the first time, the number of videos reported to the national center surpassed that of photos. The center often receives multiple reports for the same piece of content.

U.S. law requires tech companies to flag cases of child sexual abuse to the authorities. Apple has historically flagged fewer cases than other companies. Last year, for instance, Apple reported 265 cases to the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, while Facebook reported 20.3 million, according to the center’s statistics. That enormous gap is due in part to Apple’s decision not to scan for such material, citing the privacy of its users.

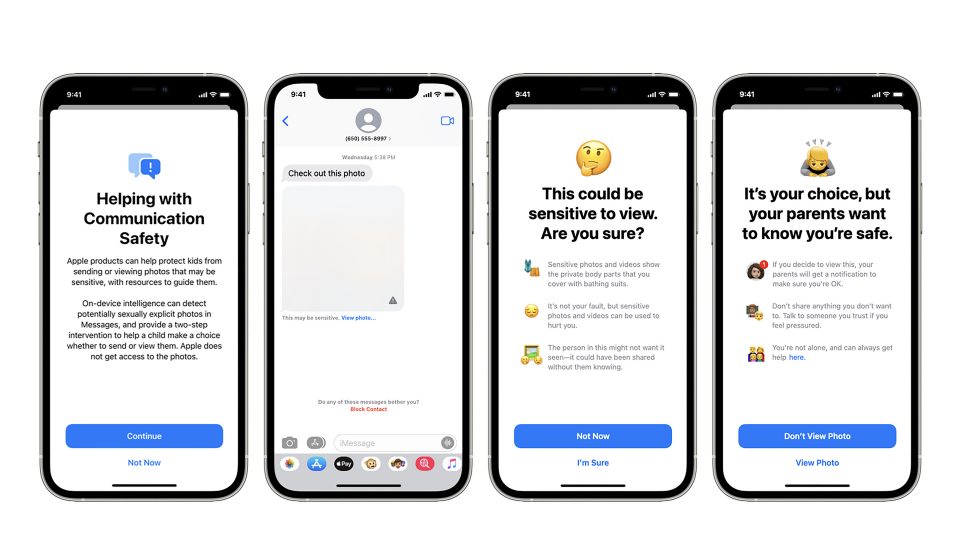

Apple’s other feature, which scans photos in text messages, will be available only to families with joint Apple iCloud accounts. If parents turn it on, their child’s iPhone will analyze every photo received or sent in a text message to determine if it includes nudity. Nude photos sent to a child will be blurred, and the child will have to choose whether to view it. If children under 13 choose to view or send a nude photo, their parents will be notified.

Green said he worried that such a system could be abused, because it showed law enforcement and governments that Apple now had a way to flag certain content on a phone while maintaining its encryption. Apple has previously argued to the authorities that encryption prevents it from retrieving certain data.

“What happens when other governments ask Apple to use this for other purposes?” Green asked. “What’s Apple going to say?”

Neuenschwander dismissed those concerns, saying safeguards are in place to prevent abuse of the system and that Apple would reject any such demands from a government.

“We will inform them that we did not build the thing they’re thinking of,” he said.

The Times reported this year that Apple had compromised its Chinese users’ private data in China and proactively censored apps in the country in response to pressure from the Chinese government.

Hany Farid, a computer science professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who helped develop early image-hashing technology, said any possible risks in Apple’s approach were worth the safety of children.

“If reasonable safeguards are put into place, I think the benefits will outweigh the drawbacks,” he said.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.