PORT VILA, 03 JULY 2019 (VANUATU DAILY POST)—Vanuatu Ministry of Foreign Affairs, International Cooperation and External Trade has informed the people of Vanuatu of the outcome of the recent maritime boundary talks with France.

The second round of maritime boundary negotiations between Vanuatu and France took place in Brussels, Belgium, on 24- 25 June 2019.

This follows the first historic maritime boundary negotiation which was held in Sydney on February 2018 after France finally agreed to engage in talks with Vanuatu to resolve the outstanding maritime boundary issue.

The Vanuatu Government delegation was led by Vanuatu’s newly-appointed Special Envoy on Maritime Boundary Delimitation, who is also Chief Negotiator, MP Johnny Koanapo, and included Kiel Loughman, the Acting Attorney General, Vanuatu’s Ambassador to France, John Licht, Roline Tekon, Head of the Treaties and Convention Division of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Dreli Solomon, 1st Secretary to the Embassy to France, and Toney Tevi, Head of the Maritime and Oceans Affairs Division of the Department of Foreign Affairs.

Since the first round of negotiations in 2018, both Vanuatu and France have in accordance with the rules of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) exchanged their base points for calculating their baselines. Base points are necessary to calculate baselines, which UNCLOS uses as the fundamental basis from which the ocean territorial claims of states are justified.

The Vanuatu delegation has now sought explanation and clarification on a number of the base points proposed by France. The French delegation, while content with almost all the base points proposed by Vanuatu, has also requested clarification on a few of these base points. These clarifications will have to be exchanged before the next round of negotiations.

The Chief Negotiator also raised additional issues of national concern regarding maritime and marine-related activities of France within the shared maritime space between the countries.

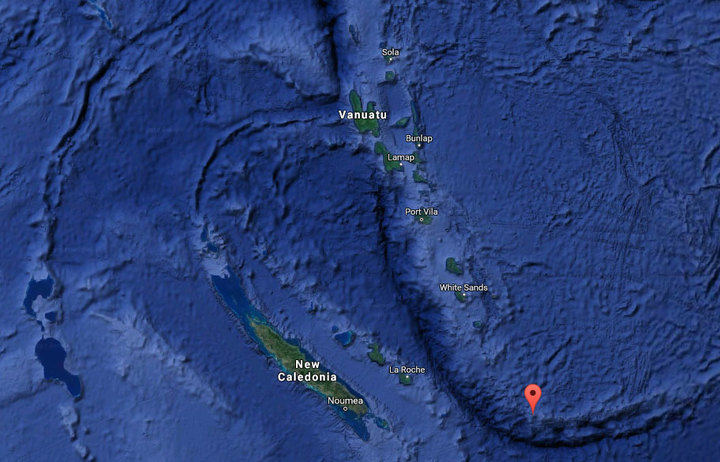

These include the dispute over ownership of Mathew and Hunter Islands, the unilateral declaration by New Caledonia of a Marine Park which covers a large section of the disputed waters around Mathew and Hunter, and the recent unauthorized entry of French Navy vessels into Vanuatu waters.

These issues were discussed and both parties have agreed to work together in the spirit of friendship to address these additional concerns.

Ralph Regenvanu, Foreign Minister of Vanuatu, said, “The second round of negotiations has made good progress on some areas, while in other areas the Government might need to consider alternative ways to address the issues. The outcome of the meeting reflects the good and long-standing relations between the Government of Vanuatu and France”.

Vanuatu and France have agreed on the outcomes of the second round of negotiations and have agreed that the third round of negotiations should be held in Sydney either before the end of this year or early in 2020.

The importance of “Baselines” in determining maritime boundaries.

Article 5 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) — “Normal baseline” — states that “the normal baseline for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea is the low-water line along the coast as marked on large-scale charts officially recognized by the coastal State”.

Article 47 (“Archipelagic baselines”) states that, “An archipelagic State may draw straight archipelagic baselines joining the outermost points of the outermost islands and drying reefs of the archipelago provided that within such baselines are included the main islands and an area in which the ratio of the area of the water to the area of the land, including atolls, is between 1 to 1 and 9 to 1”.

In international law, UNCLOS has been described as the “constitution” governing the legal rights and obligations of coastal states over the sea areas surrounding and adjacent to their land areas.

Under UNCLOS, a coastal state has the right to claim a series of “marine zones” in the sea areas that border its land territory.

There are three stages in the process by which a state can claim these zones. Firstly, a state has to establish “baselines” or geographical starting points from which it can then measure the outer limits of the different zones it wishes to claim. Articles 55 and 57 of CLOS provide for the “exclusive economic zone”, or EEZ, which extends up to 200 nautical miles from a state’s baselines.

The legal rights of a state within its EEZ are described in Article 56 as including,

(a) sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources, whether living or non-living, of the waters superjacent to the seabed and of the seabed and its subsoil, and with regard to other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone, such as the production of energy from the water, currents and winds;

(b) jurisdiction … with regard to:

(i) the establishment and use of artificial islands … and structures;

(ii) marine scientific research;

(iii) the protection and preservation of the marine environment.

The state does not have any legal competence over the airspace over the EEZ, however, and ships belonging to other states have ‘freedom of navigation’ in this zone. In addition to these rights, other states can also lay submarine cables and pipelinesand enjoy ‘other internationally lawful uses of the sea related to these freedoms’ in the EEZ (article 58).

The outermost marine zone able to be claimed by a coastal state is the “continental shelf”. As defined by article 76(1) of UNCLOS, “the continental shelf of a coastal State comprises the seabed and subsoil of the submarine areas that extend beyond its territorial sea throughout the natural prolongation of its land territory to the outer edge of the continental margin, or to a distance of 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured where theouter edge of the continental margin does not extend up to that distance”.

Where the ‘natural prolongation of land territory’ means that the continental margin extends beyond the outer limits of the EEZ (that is, beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines), Article 76 places an outer limit on the continental shelf zone that can be claimed by a state of 350 nautical miles from the baselines.

Article 76 also requires that a claim for a continental shelf with an outermost limit of more than 200 nautical miles from the baselines is to be done ‘on the basis of the recommendations’ of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf established under Annex II of CLOS and according to the criteria provided in paragraphs 4 to 6 of the article.

A state has sovereign rights to explore and exploit the natural resources of the continental shelf and no other state can undertake such activities in this zone without the consent of that state.

The third stage in the process by which a state can claim marine zones in the sea areas that border its land territory is the one of particular relevance to the current negotiations: the establishment of maritime boundaries with other states where the proximity of the two states creates overlapping claims to their respective marine zones.

This third stage in the process is only entered into in instances where the coastlines of two states face each other across the sea (are “opposite”) or are beside each other on the one landmass (are “adjacent”) and are close enough that the outer limits of one or more of the marine zones both states can claim overlap.

In these instances, the general rule is that the two states should enter into an agreement to establish their maritime boundaries (articles 15, 74 and 83 of CLOS).

Where the parties cannot come to an agreement ‘within a reasonable period of time’ (articles 74 and 83), they can ‘resort to the procedures provided for in Part XV (Settlement of Disputes)’, which include taking the matter before the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea or the International Court of Justice.

In either case, the states are required in the period before an agreement is reached to come to some sort of temporary workable arrangement in good faith (articles 74 and 83).

Source: PACNEWS