By Scott Waide – EM TV, Lae

The crusty old teacher with more than 30 years under his belt sits on his hauswin and reaches for a buai. He is engaged in a serious conversation about education standards in the Oro Province.

“I’m talking about standards that have declined,” he emphasises in impeccable English. “I didn’t say declining. They have declined.”

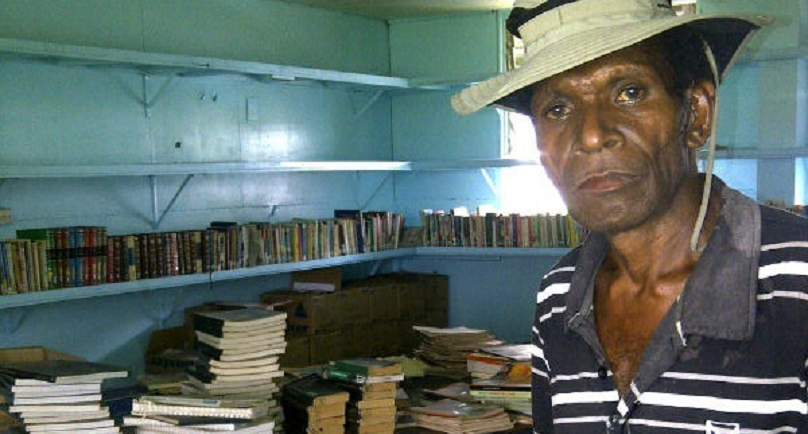

John Somboba, a veteran educationist, is known by former students for his boundless energy and legendary temper. But those who know him also know that Somboba has always demanded the best from his students and gets very angry when the best isn’t forthcoming.

In more recent years, his ire has been directed at Oro’s provincial education division and its political leaders. He has good reason to be angry: in 2011, only one student from the entire province went on to a higher education institution based on merit. It’s a shocking statistic.

“It’s not because Oro students aren’t intelligent,” Somboba says.

The academic results produced by the students are a reflection of the disarray within the provincial education division. For 10 years, the standards and measurements section that is responsible for appraisals and the monitoring teacher performance has been relatively inactive. Schools have not been inspected. Teachers have not been appraised. This has a direct impact on motivation and education standards.

Another senior teacher points out that younger teachers who are serious about building a career have very little hope of being promoted in the Oro Province because their work isn’t evaluated by an inspector.

“There’s a lack of direction by the education management,” he says.

Others point out that those who are now at the helm don’t have the management and planning skills required to tackle the myriad of problems affecting education in the province.

There appears, however, to be a faint glimmer of hope. One year into his new job, Charles Soso, the man now responsible for standards and monitoring, has brought in four new inspectors. In 2011, with limited funds, he was able to conduct inspections of at least 120 of Oro’s 300 plus primary schools. But he knows that’s not good enough.

Soso also believes that the changes in teaching methods and content, as per Papua New Guinea’s education reforms aren’t being implemented.

“The teaching methods are different from the days when we were growing up,” he says. “There’s a knowledge gap.”

He also believes that what is taught in some schools isn’t consistent with what students are being tested in national exams. However, senior education planners like Soso don’t really know the extent of the problems because of the lack of reliable information.

Another long-serving teacher says the poor reading and writing skills exhibited by grade nine and ten students, is a direct result of the elementary school system. Teachers for the elementary school system don’t attend the normal teacher training colleges. They are instead put through a six-weeks training course and then sent back to their communities to work.

“How can you expect a grade ten leaver who didn’t do well in school to lay a solid foundation for the education of a child?” asks Carson Gandari, a 35-year veteran of the teaching service.

In a the classes he teaches, students have difficulty reading, writing and understanding the English language. Poor language skills affects their ability to perform well in almost every other subject.

Gandari is one of the many who has seen education standards plummet to near hopeless standards. As a teacher, he has helped to mold bureaucrats, politicians, journalists and doctors. For this teacher, poor education standards affects his pride and the pride of his province.

“I can’t do that anymore and I hang my head in shame. When the last of our teachers and the last of our doctors are gone, we will have to import people from outside to run this province.”