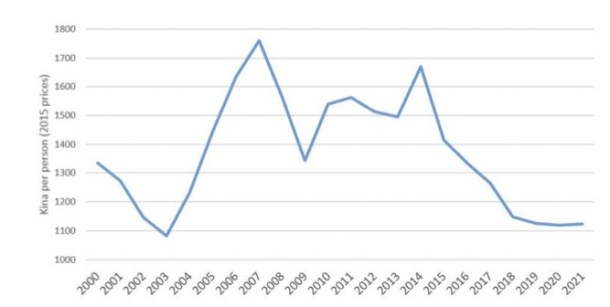

Image: Government Total Revenue per capita. Source: DEVpolicy blog

The Papua New Guinea government, faced with falling revenue, cut back sharply on core services in the 2017 Budget says Stephen Howes, Director of the Development Policy Centre at the Australian National University. But MP funding is at five times its 2012 level.

Government total revenue per capita Source: Devpolicy blog

Papua New Guinea’s 2017 Budget has some pretty simple maths behind it.

With revenue projected to be slightly up, and borrowing slightly down, total expenditure is virtually unchanged when compared with the supplementary 2016 Budget, which scaled back both revenue and expenditure from their original 2016 Budget levels.

ANU’s Stephen Howes

Salaries and interest are also unchanged, which seems optimistic given a mounting debt stock and threats of strikes.

Also unchanged is the amount of funds for Members of Parliament (MPs). An extra K550 million had to be found to pay for elections and APEC. Something had to give.

Services cut

What has been cut is core services. Health is to be cut in 2017 by K315 million (21 per cent), education by K80 million (6 per cent) and transport by K128 million (12 per cent).

Even law and justice, a government priority, gets a K108 million (9 per cent) cut. All of these cuts are before inflation, and are compared to the scaled-back supplementary 2016 allocations.

How could have these cuts to core services have been avoided? It might be argued that the government should have borrowed more. Yet the government seems to be borrowing about as much as it can (as it should, given the drop in revenue).

The International Monetary Fund, World Bank and Asian Development Bank could be tapped for further budgetary support lending, but that would require a reform program.

The debt-to-revenue ratio is approaching historic highs:

Papua New Guinea’s debt-revenue ratio Source: Devpolicy Blog

Members of parliament

Core services could have been better protected if MP funds had been reduced. These funds are spent at the district, provincial and sub-district level, through programs such as the District Services Improvement Program (DSIP), which is mainly under the control of PNG’s MPs.

Spending on MP funds Source: Devpolicy blog

MP funds were much smaller in the past, but they have been ratcheting up, first in 2006 and 2007, and then in 2012. There have been subsequent declines in both cases, but not back to their earlier levels.

PNG has more reliance on spending through MPs than any other country in the world. It spends as much on MP funds as it does on health, and more than it does on law and justice, or on transport.

Whereas hospital funding as a whole in PNG is 16 per cent below the 2012 level, MP funding is at five times its 2012 level.

‘Falling or stagnant revenue is an underlying problem.’

Perhaps it is unrealistic to think that MP funding might be cut before the election [scheduled for July 2017]. But the increased share of MP funding in total expenditure from just 2 per cent in 2012 to 9 per cent now is a major fiscal shock, squeezing out funding for core services.

Revenue

Falling or stagnant revenue is an underlying problem. While the budget does contain some tax reforms, the trajectory for revenue is negative.

Adjusted for inflation, revenue falls over the forward estimates. Adjusted for population growth, revenue is already back at 2004 levels.

‘While tax compliance can be improved, the underlying problem is slow economic growth.’

By 2021, it will be at the lowest level seen this century. PNG Treasury is renowned for its conservative revenue forecasts. But clearly, this is not a basis on which core services can be adequately resourced.

While tax compliance can be improved, the underlying problem is slow economic growth, which is projected to be just above population growth for the next five years. This is too pessimistic.

Even without any further resource projects, PNG ought to be able to grow its GDP by 5 per cent per year or more. Exchange rate depreciation and a range of economic reforms would rebuild economic confidence and allow growth and revenue to accelerate without having to wait for the next resource project.

But all of this seems to have been put in the too-hard basket. The exchange rate has been fixed since May, and the regulation of foreign exchange is increasingly intrusive.

PNG may have to wait until after the 2017 elections for reforms to revive growth and prioritise core services.

Professor Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University. He writes for the Devpolicy Blog.

Copyright © 2016 Business Advantage International.