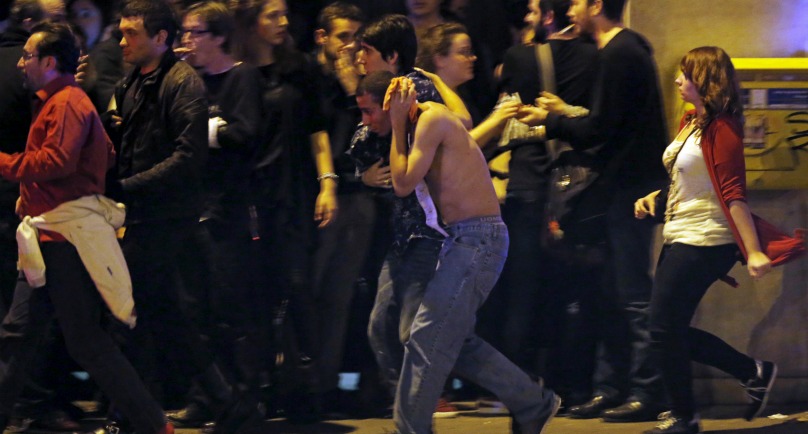

Image: An injured man holds his head as people gather near the Bataclan concert hall following fatal shootings in Paris, France, November 13, 2015. REUTERS/Christian Hartmann

By Geert De Clercq and Marine Pennetier

PARIS (Reuters) – It should have been a Friday night like any other in Paris, with locals and visitors watching a show, enjoying a good meal or shrugging off the cares of the week over a relaxed drink.

But for the second time in less than a year, France and the world are asking how militants could strike at the heart of the city, including at a concert hall just a few hundred steps from January’s deadly attack on the satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo.

“As we went to our car we saw dozens of people running out of the Bataclan,” local resident Caterina Giardino, an Italian national, said of the 19th century theatre-turned-music venue where gunman clad in black killed at least 87 people.

“Many of them were covered with blood, people were screaming,” she added, sitting on a bench with a friend and recalling how one young man emerged from the concert hall with the bloody imprint of a hand on his shirt.

Islamic State has claimed responsibility for the gun and bomb assaults on the concert hall, a Sport stadium and restaurants as a response to France’s role in the U.S.-led coalition fighting in Syria.

The first blast was heard at 9.17 p.m. (2017 GMT) outside the Stade de France national Sport stadium, where France and Germany were playing a friendly soccer game in the presence of President Francois Hollande. Spectators distinctly heard a second detonation about two minutes later.

About 10 km (6 miles) away, inside the Bataclan music venue, California-based rock band Eagles of Death Metal were on stage promoting their fourth album when the audience began to notice something was not right.

“I saw the musicians drop their instruments and escape towards the backstage,” said Julien Pearce, a reporter for Europe 1 radio who was in the theatre.

“I turned back and saw at least three gunmen with rifles, Kalashnikovs. So immediately, the crowd dropped to the ground, facing the ground. There was some trampling as some people tried to reach the stage at all costs … Two persons stood up too early and were shot at and dropped dead, just in front of me.”

As the gunman paused to reload, Pearce managed to sneak round the side of the stage and out through an exit.

Outside the venue, there was panic. Paris police chief Michel Cadot told local television the gunman had sprayed the terraces of nearby cafes with bullets before entering the hall.

One 23-year-old who gave his name only as Arik was returning to his apartment near the Bataclan when the attacks started.

“When I got to the Bataclan, I saw a lot of cops looking panicked. They were running everywhere.

“Two guys were on the ground. One of them was wounded by a glass shard in his stomach. He was alone. Someone had passed him a first aid kit but nobody was helping him… When I got to my street, I saw people crying. It was like we were in a war zone.”

Dozens of ambulances raced to the venue. Soldiers in camouflage were gathering on the nearby Bastille Square.

Shortly after midnight Paris time, a handful of loud blasts were heard coming from the theatre, not long after Hollande had issued a statement saying operations were under way to free those still in the theatre.

“As I got home, I heard the shots (of special forces raiding the Bataclan),” said Arik. “It seemed to never stop. We could hear people shouting outside, echoes… We felt the cops were totally overwhelmed. It was chaos.”

The police assault was extremely difficult, Cadot said.

“The terrorists who locked themselves in one of the floor had explosives belts which they detonated, and the four were killed during the assault,” he said.

Hollande, who was quick to declare a state of emergency, has described the assault as an act of war and said France will be “merciless” in its response.

For his government, as for the French, the coming days are likely to raise as many questions as answers.

Why was France yet again targeted above other members of the U.S.-led coalition fighting in Syria?

Could the authorities, who already had the country on a heightened level of security and had promised improved surveillance after the Charlie Hebdo attacks, have done more to prevent this new assault?

And will the French, who in January came out on the streets in their hundreds of thousands to mourn the Charlie Hebdo victims, do the same a second time?

Sharon Kheloui, 40, a bartender at the “A la folie” bar on rue Oberkampf near the Bataclan concert, couldn’t restrain her sadness and frustration.

“They were just kids. Teenagers who only wanted to have fun,” she said. “Sometimes my children go to the Bataclan. Now we must start thinking about how risky it is.”

(Additional reporting by Nicolas Delame, Bate-Felix Tabe-Tabi, Matthias Blamont and Ingrid Melander in Paris; writing by Mark John and Sonya Hepinstall; editing by Paul Taylor and Peter Millership)

Copyright 2015 Thomson Reuters. Click for Restrictions.