by Rohan Fox

The first article in this series showed that of the 281 University of Papua New Guinea (UPNG) students from the School of Business and Public Policy surveyed in May 2021 about their attitudes to COVID-19 vaccination, 46% had not decided whether they would like to be vaccinated. Just 6% said they would like to be vaccinated against COVID-19, while 48% were against vaccination. This blog looks at the people and institutions from whom respondents trust to receive information on COVID-19.

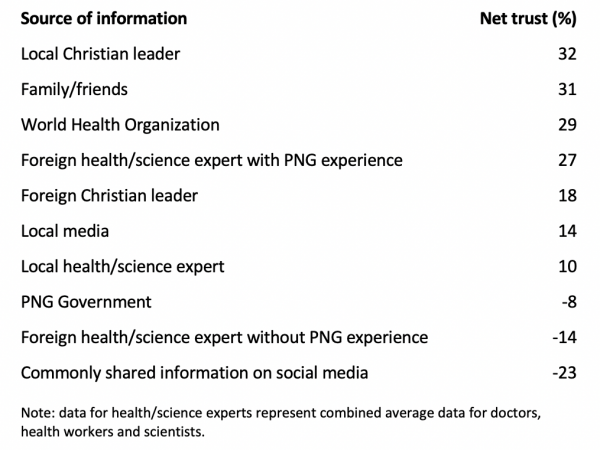

Many students noted that they wanted more information on COVID-19, vaccinations, risks, and side effects. In order to make informed choices, people need access to information that is not only accurate but from trusted sources. Although the respondents are young, and not in the at-risk cohort, their views on COVID-19 and trust are still informative. So we asked the students to rank a number of sources from “strongly distrust” (1) to “strongly trust” (5), based on how confident they would be to use the information they received on COVID-19 from those sources. From their answers, we created a measure of net trust: the percentage who said they trusted or strongly trusted information from a particular source, minus the percentage of students who said they distrusted or strongly distrusted information from that source.

Zenger and Folkman (2019) suggest that there are three key determinants of trust – (positive) relationships, expertise, and consistency. In their research, relationships were found to be the most important, consistency the least. This hierarchy corresponds well to the most trusted sources of COVID-19 information we asked about, including local Christian leaders (positive close relationship), friends/family (positive close relationship), and the World Health Organization (WHO – expertise).

The responses showed that international institutions and experts were both some of the most-trusted and least-trusted, based on whether they had PNG experience or not. The students surveyed were taught by Australian and foreign lecturers under the UPNG–ANU partnership. For this reason, their trust of international institutions may be higher than other UPNG students, or the rest of the PNG population.

The figure below shows the responses for the WHO (one of the most-trusted organisations) and social media (the least-trusted source of information).

Twice as many “trust” or “strongly trust” the WHO as social media, but both groups have a large share of “neutral” responses. Indeed, for every institution, except for family and friends, the average level of trust was “neutral” or lower. (For family and friends it was “trust”.) Even those institutions that are relatively more trusted in PNG are not highly trusted. Several students noted their skepticism of various sources of information and the difficulty they had in determining who to believe.

Data has shown that distrust of institutions of authority and vaccine hesitance goes together. There may be various legitimate reasons to distrust authority. In PNG, many are aware of the corruption that has occurred within institutions of authority. In the US, Black Americans express higher than average vaccine hesitancy, and higher institutional distrust, some of whom note past unethical treatment by medical authorities. For many individuals, sharing stories from within a person’s own community can be more persuasive than appeals to “authoritative” facts. While a lack of trust in authority is certainly not the only factor at play, many respondents noted the lack of stories they had heard from their own community or wider PNG on the personal impact of COVID-19 or vaccines.

As such, for many, sharing Papua New Guinean stories about those impacted by the COVID-19 virus, or those who decided to take the vaccine (like this formerly vaccine-hesitant doctor for example) and what side-effects they had, could be more persuasive than high-level global data. If these stories are told by friends, family, or local Christian leaders they may be received as more trustworthy still.

While average trust in most sources of information is “neutral”, the survey does show that many do still value the expertise of institutions like the WHO. As such, a combination of approaches – telling more Papua New Guinean stories, along with sharing the latest data and facts from those with expertise (and ideally local knowledge) – may be most successful to demonstrate trustworthiness, spread accurate information on COVID-19 and vaccination, and optimise health outcomes.

Author notes Sincere thanks to the respondents who took part in this survey.

The World Health Organization (WHO) endorses a number of COVID-19 vaccines, including the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine available in PNG, as safe and effective at protecting people from the risks of COVID-19. According to Oxford University, as of June 2021, 2.6 billion people have been vaccinated against COVID-19. The risk of vaccination is classified by the WHO as very low.

This is the second article in a #vaccine hesitancy and trust series. You can read the first article at devpolicy.org.

Disclosure: This research was undertaken with the support of the ANU-UPNG Partnership, an initiative of the PNG-Australia Partnership. The views represent those of the author only.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University.

Rohan Fox is a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre. He lectured in the economics program at the University of Papua New Guinea in 2015, 2016, and 2020.