By Jim Tankersley and Alan Rappeport c.2021 The New York Times Company.

WASHINGTON — The Biden administration and top Democrats in Congress began detailing plans for significant changes to how the United States and other countries tax multinational corporations as they look for ways to raise revenues and finance President Joe Biden’s $2 trillion infrastructure proposal.

On Monday, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen threw her support behind an international effort to create a global minimum tax that would apply to multinational corporations, regardless of where they locate their headquarters. Such a global tax, she said, could help prevent a “race to the bottom” in which countries cut their tax rates in order to entice companies to move headquarters and profits across borders.

“Together, we can use a global minimum tax to make sure the global economy thrives based on a more level playing field in the taxation of multinational corporations,” she said. The effort is aimed at “making sure that governments have stable tax systems that raise sufficient revenue to invest in essential public goods and respond to crises, and that all citizens fairly share the burden of financing government.”

At the same time, Democrats in Congress released their own proposal to add teeth to the de facto minimum tax that the United States already imposes on income earned abroad — one that would apply to American multinational companies regardless of what the rest of the world does. The proposal could raise as much as $1 trillion over the next 15 years from large companies by requiring that they pay higher taxes on profits they earn overseas, according to analyses of similar plans.

Yellen’s support for a global minimum tax could help catalyze an agreement being worked out through the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which seeks to reduce companies’ practice of booking profits in low-tax “haven” countries to avoid higher tax bills elsewhere. Negotiators are discussing a range of possibilities for such a plan, but they have not settled on several crucial details, including the rate of the minimum tax.

The focus on raising taxes for large companies comes as the Biden administration begins its push to sell a $2 trillion infrastructure plan and finance it with higher taxes. Biden’s proposal includes raising the U.S. corporate tax rate to 28% from 21% and a variety of changes to international tax law, all meant to force companies to pay more to the Treasury after a plunge in corporate tax revenues spurred by President Donald Trump’s signature 2017 tax cuts.

Democrats and White House officials say that their goal is to ensure companies pay their fair share and that they do not move jobs and profits abroad to avoid paying taxes in the United States.

But some tax experts, along with large business lobbying groups, say the proposals could hobble U.S. corporations on the global stage by forcing them to pay significantly higher tax rates than their competitors pay. That could be true even if global negotiators eventually agree to a worldwide minimum tax — because that tax rate could still be lower than what companies pay in the United States.

If the Democratic plans succeed and Yellen and her global counterparts reach agreement, “there could be a cogent international tax system” with some effective incentives for investments in the United States, said Danielle Rolfes, a former international tax counsel for the Treasury Department in the Obama administration who is now a leader of KPMG’s international tax practice in Washington.

But, she said, “I would be concerned, if the rates get too high, that the U.S. might have competitiveness issues.”

Sen. Patrick J. Toomey, R-Pa., said Yellen’s call for a global minimum tax was an admission that Biden’s plan to raise the corporate tax rate to 28% would make U.S. companies less competitive.

“This is why Secretary Yellen is imploring other developed countries to punish their workers and businesses with their own tax increases,” Toomey said in a statement. “‘Race to the bottom’ is the way the Biden administration describes competition among developed countries to get to a tax code that attracts investment and maximizes growth.”

Biden dismissed that view Monday, saying U.S. companies could afford to pay a higher tax rate given many paid no taxes over the past several years.

“You have 51 or 52 corporations of the Fortune 500 that haven’t paid a single penny in taxes for three years,” he said. “Come on, man. Let’s get real.”

And Yellen, in remarks before the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, noted that many developing and middle-income countries were struggling financially, in part because of insufficient tax revenue. That has made it harder for them to invest in robust rollouts of coronavirus vaccines, which she warned could hurt the global economy as the pandemic continues.

“The result will likely be a deeper and longer-lasting crisis, with mounting problems of indebtedness, more entrenched poverty, and growing inequality,” Yellen said, estimating that as many as 150 million people could be pushed into extreme poverty this year. “This would be a profound economic tragedy for those countries, one we should care about.”

At issue is how governments should tax income that multinational companies earn across borders. Large firms increasingly operate in multiple nations: Amazon sells to shoppers in Europe, for example, and Morgan Stanley offers financial services in China.

With operations spread across multiple countries, many companies seek to reduce their tax bills by locating operations — or simply booking profits — in low-tax jurisdictions like Bermuda or Ireland. When Republicans passed their sweeping tax law in 2017, supporters said it would help to curb that practice and encourage domestic investment, both by reducing the corporate tax rate in the United States and by setting up a new system for taxing income earned abroad, including a measure that was meant to be like a minimum tax for all global income.

But Democrats say the law and the administration’s use of the tax did the opposite, giving companies new incentives to locate factories and profits abroad. Both the plan Biden sketched out last week and a new proposal released by three Democratic senators Monday would seek to reverse those incentives, taxing offshore income more aggressively and offering new targeted benefits for companies that invest in research and production at home.

The proposal would increase the rate of the 2017 minimum tax and change how it is applied to income that corporations earn in various countries overseas, effectively forcing many companies to pay the tax on more of their income, while offering new targeted tax relief linked to domestic investments.

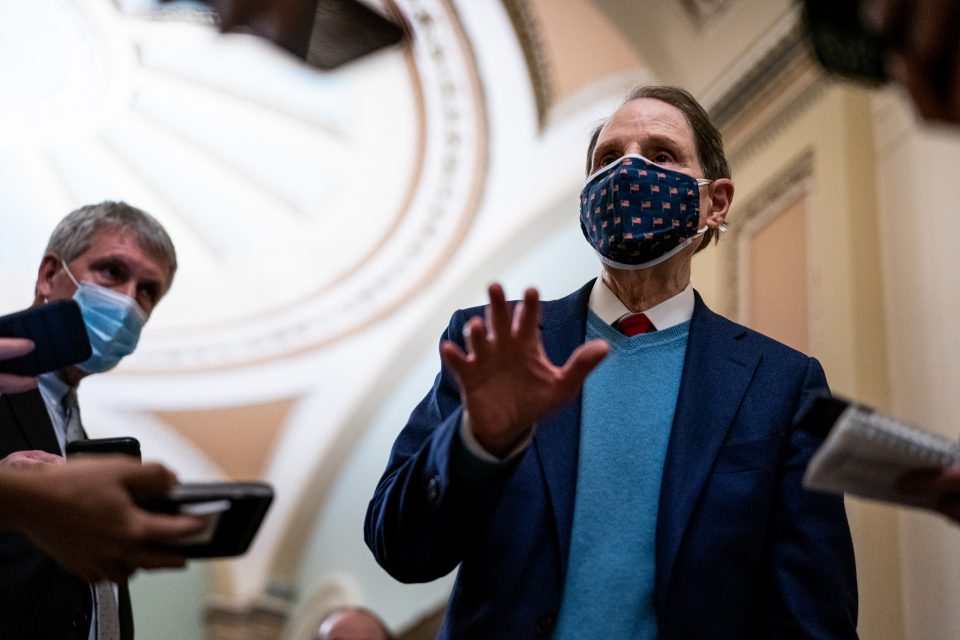

The Senate plan comes from Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., who is in charge of writing tax legislation as chairman of the Finance Committee, and two Democratic colleagues: Sen. Sherrod Brown of Ohio and Sen. Mark Warner of Virginia.

The presence of Brown, one of the most progressive Democrats on tax issues in the Senate, and the more centrist Warner as authors suggests the Wyden plan could attract widespread support in a Democratic caucus that most likely cannot afford to lose a single vote for Biden’s infrastructure plan.

Adam Looney, a former Treasury Department tax official in the Obama administration who is now the executive director of the Marriner S. Eccles Institute for Economics and Quantitative Analysis at the University of Utah, praised the senators’ proposal. “The plan retains the now-familiar international tax regime,” he said, “but proposes to reform several lopsided tax breaks that provide rich benefits for international corporations without much in the way of investment or jobs in the U.S.”

But Republicans, the leading business lobbying group and some tax experts panned the proposal and defended the Trump system as one that worked.

The 2017 law “worked to improve a system that no one felt was working and struck a balance between the need for companies to be able to compete in the global economy while protecting the U.S. tax base,” said Caroline Harris, the vice president of tax policy at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. “Today’s proposal to increase international taxes threatens to move us to a system even worse than where we started, to the detriment of economic growth, competitiveness and job creation.”

Tax experts expressed similar concerns about enforcing the kind of global minimum tax Yellen is calling for and about what that might mean for American companies.

“It’s administratively impossible to execute and it requires all countries in the world to hold hands,” said Peter Barnes, a lawyer at the tax firm Caplin and Drysdale who was previously a senior international tax counsel for General Electric. “Unless they can get 90% of the world’s countries to adopt it, countries will view exempting themselves from the system as a great way to create a potentially significant competitive advantage.”

Other experts said the timing of the two efforts could pose challenges for U.S. businesses, particularly if Biden succeeded this year at overhauling the United States system of international taxation, but global negotiations take years to translate into the actual imposition of new minimum taxes elsewhere.

Any change to international taxation is far from guaranteed. The Senate proposal released on Monday is likely just the first of several plans to raise corporate tax revenue — all of which face a tricky road to passage given Democrats’ narrow margins in both chambers. And while global negotiations for a minimum tax are underway, an agreement, if reached, could take years to put in place.